Please Note:

Contents

Unusual way in which the European Union works

The Three Main Decision-Making Institutions

The Treaties - Primary Legislation

Merged Treaties - The Three Pillars of the EU

The European Union is unique. It is not a federal State like the United States of America, nor is it a purely intergovernmental organisation like the United Nations. The European Union (EU) is a family of democratic European countries working together to improve life for their citizens and to build a better world.

EU is a remarkable success story. In just over half a century, it has delivered peace and prosperity in Europe, a single European currency (the euro) and a frontier-free 'single-market' where goods, people, services and capital move around freely. It has become a major trading power, and a world leader in fields such as environmental protection and development aid.

The European Union’s success owes a lot to the unusual way in which it works.

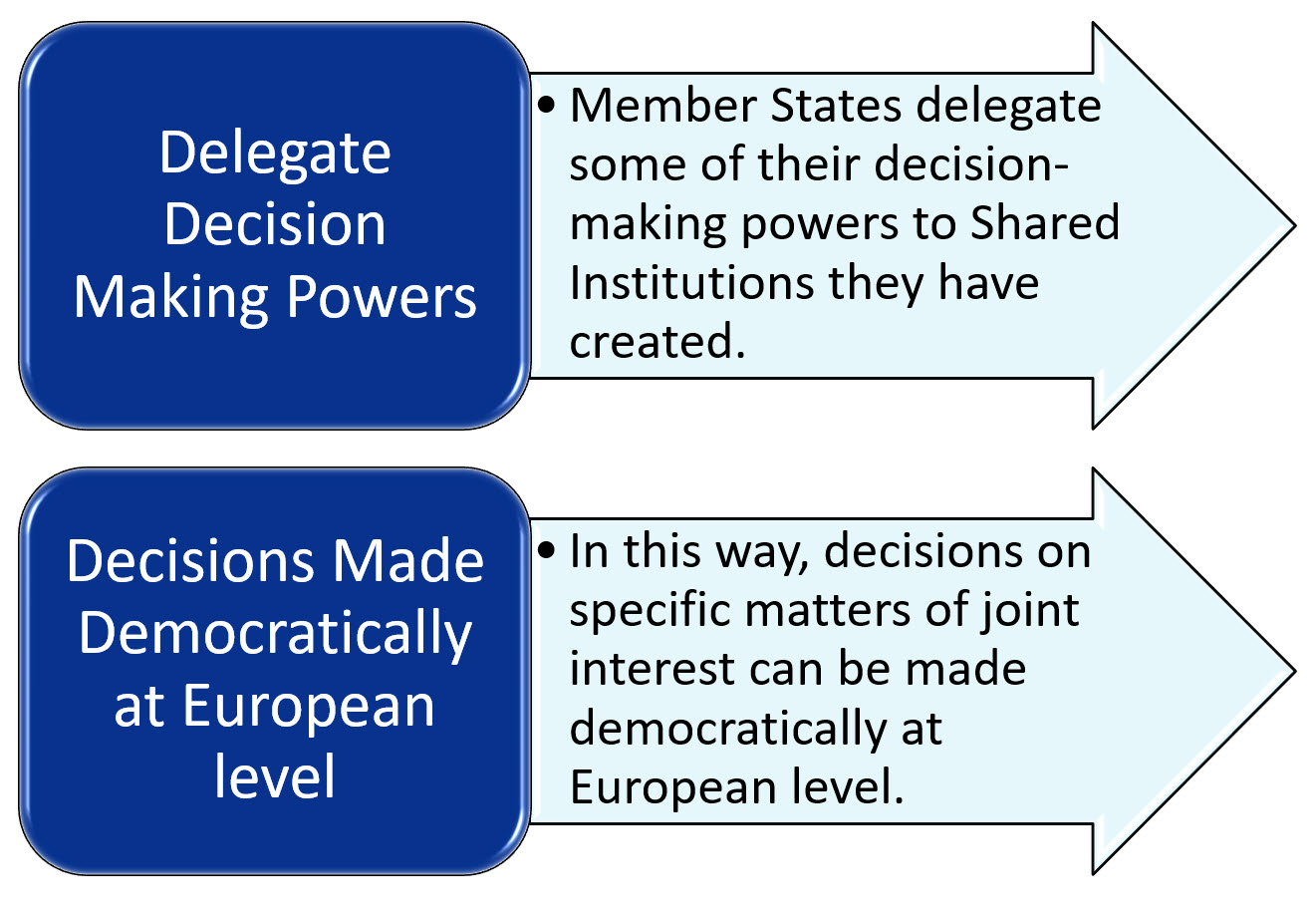

European Union works in an unusual way, because its 'member states' remain independent sovereign nations but they pool their sovereignty in order to gain a strength and world influence none of them could have on their own.

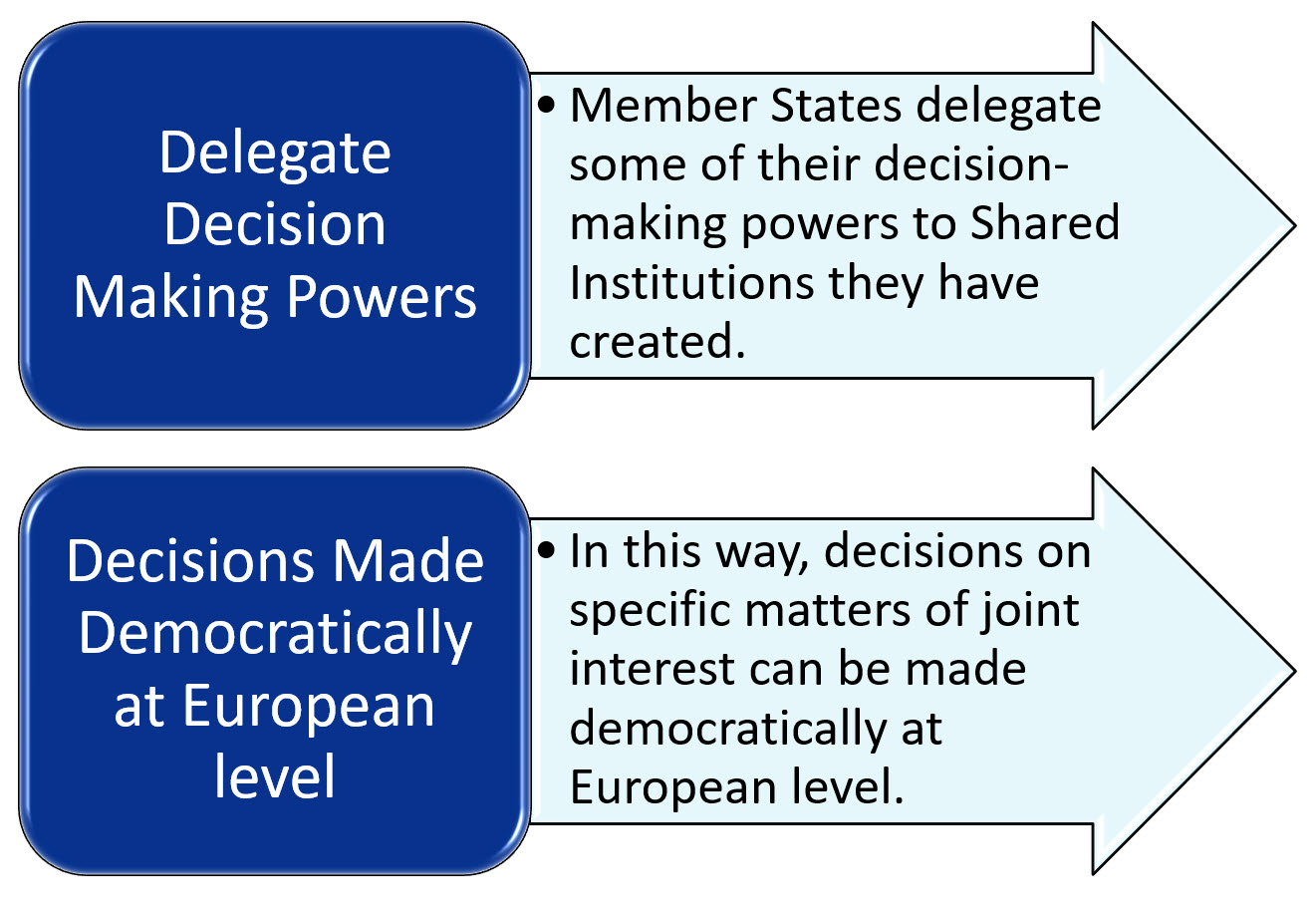

Pooling Sovereignty means, in practice, that the member states delegate some of their decision-making powers to shared institutions they have created.

In this way, decisions on specific matters of joint interest can be made democratically at European level.

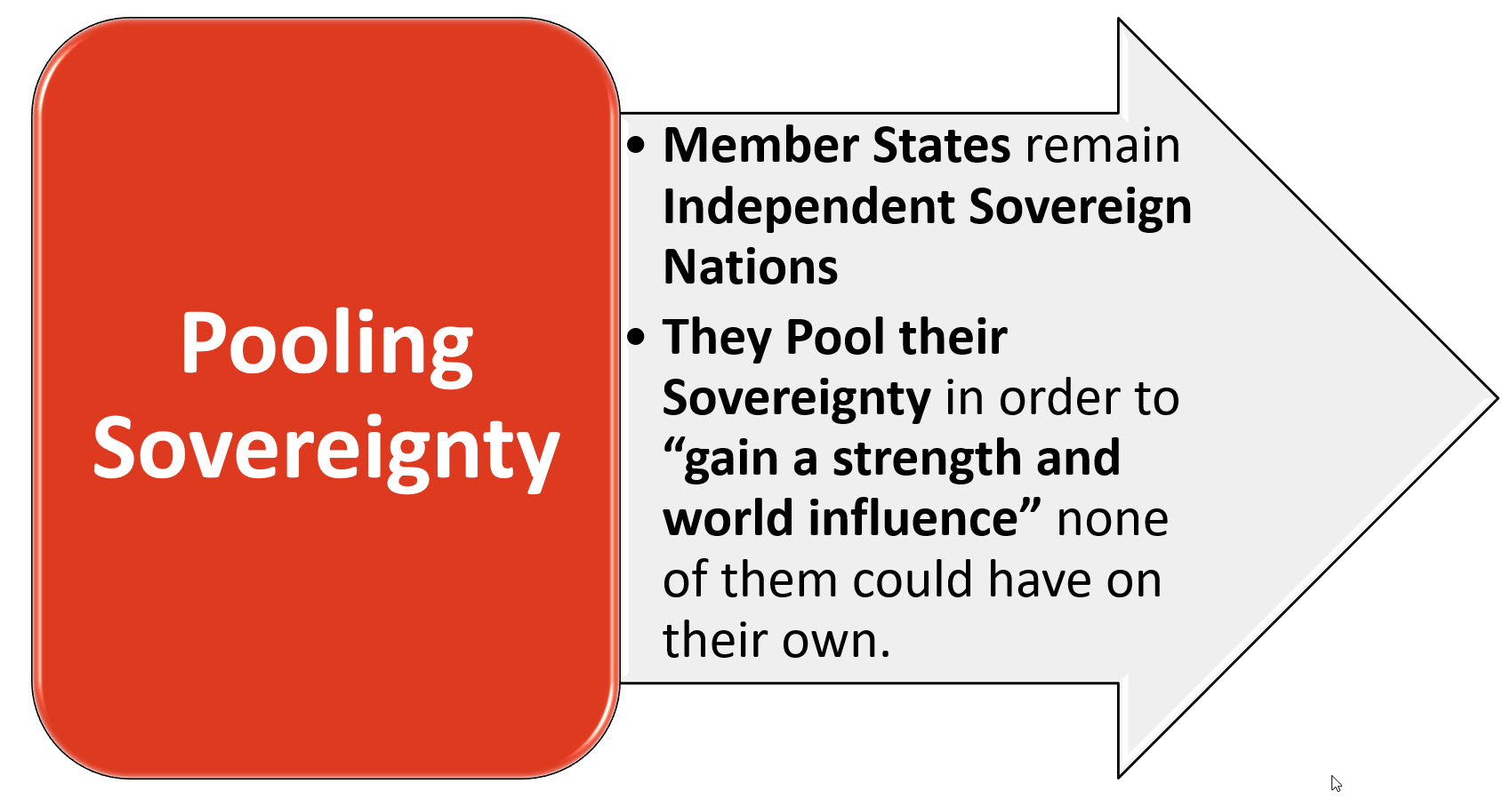

The three main decision-making institutions are:

This Institutional Triangle produces the policies and laws that apply throughout the EU.

The powers and responsibilities of the EU institutions, and the rules and procedures they must follow, are laid down in The Treaties on which the EU is founded.

The Treaties are agreed by the Presidents and Prime Ministers of all the EU Countries and then ratified by their Parliaments.

The EU is founded on four Treaties:

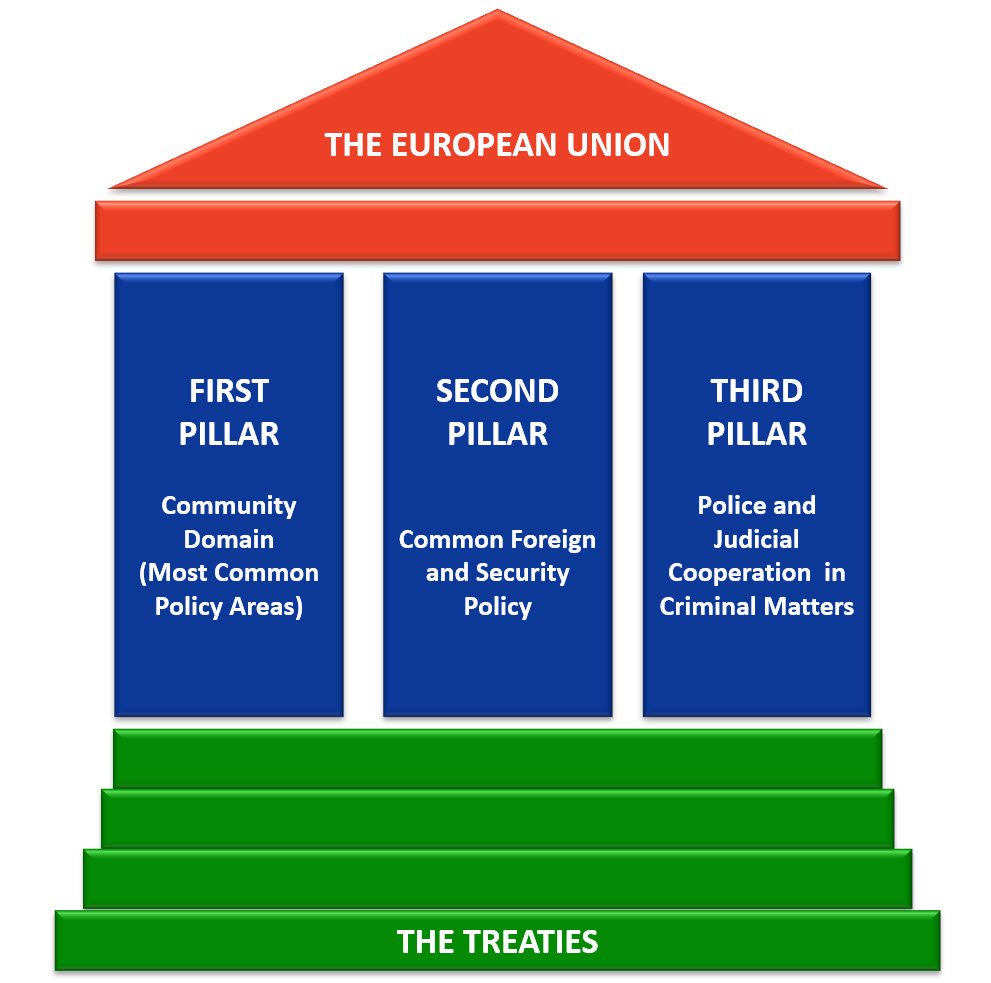

These Treaties have merged and evolved in time creating The Three Pillars of The EU.

The Treaties which are also known as The Primary Legislation have merged and evolved in time creating the Three Pillars of the EU:

This evolution is described below.

The European Coal and Steel Community(ECSC), the European Economic Community(EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community(Euratom) Treaties created the three European Communities, which is the system of joint decision-making on coal, steel, nuclear power and other major sectors of the member states' economies.

The common institutions set up to manage this system were merged in 1967, resulting in a single Commission and a single Council of Ministers.

The EEC, in addition to its economic role, gradually took on a wide range of responsibilities, including social, environmental and regional policies. Since it was no longer a purely economic community, the Fourth Treaty(Maastricht) renamed it simply the European Community (EC). As the ECSC Treaty approached expiry in 2002, responsibilities for coal and steel were progressively merged into other Treaties.

At Maastricht, the member state governments also agreed to work together on Foreign and Security Policy and in the area of Justice and Home Affairs. By adding this intergovernmental cooperation to the existing Community system, the Maastricht Treaty created a new structure with Three Pillars which is Political as well as Economic.

These Three Pillars represent the different political and economic policy areas, with different decision-making systems;

... and this is the European Union.

The Treaties are the basis for everything the EU does. They have been amended each time new member states have joined.

From time to time the Treaties have also been amended to reform the European Union Institutions and to give them new areas of responsibility.

This is always done by a Special Conference of the EU's National Governments which is called an Inter-Governmental Conference or IGC.

Key Inter-Governmental Conferences resulted in the following legislation.

The Single European Act (SEA)

The Single European Act, which was signed in February 1986 and came into force on 1 July 1987. It amended the EEC Treaty and paved the way for the single market.

The Treaty of Amsterdam

The Treaty of Amsterdam, which was signed on 2 October 1997 and came into force on 1 May 1999. It extended the pooled sovereignty to more areas involving more citizens' rights, and closer interaction on social and employment policies.

The Treaty of Nice

The Treaty of Nice, which was signed on 26 February 2001 and came into force on 1 February 2003. It further amended the other Treaties, streamlining the EU's decision-making system so it could continue to work effectively even after further enlargements.

The Draft Constitutional Treaty

The draft Constitutional Treaty, which was agreed and signed in October 2004, but has not come into force because it was not ratified by all EU countries.

The Reform Treaty

The Reform Treaty, which was agreed in principle in 2007, but will not come into force until it has been ratified by all member states.

The Treaties which are known as Primary Legislation, are the basis for a large body of Secondary Legislation.

The Secondary Legislation consists mainly of regulations, directives and recommendations adopted by the EU institutions.

These laws, along with EU policies in general, are the results of decisions taken by the Institutional Triangle mentioned above.

These laws have a direct impact on the lives of EU citizens.

The main forms of EU law are;

Regulations are directly applicable throughout the EU as soon as they come into force without further action by the Member States.

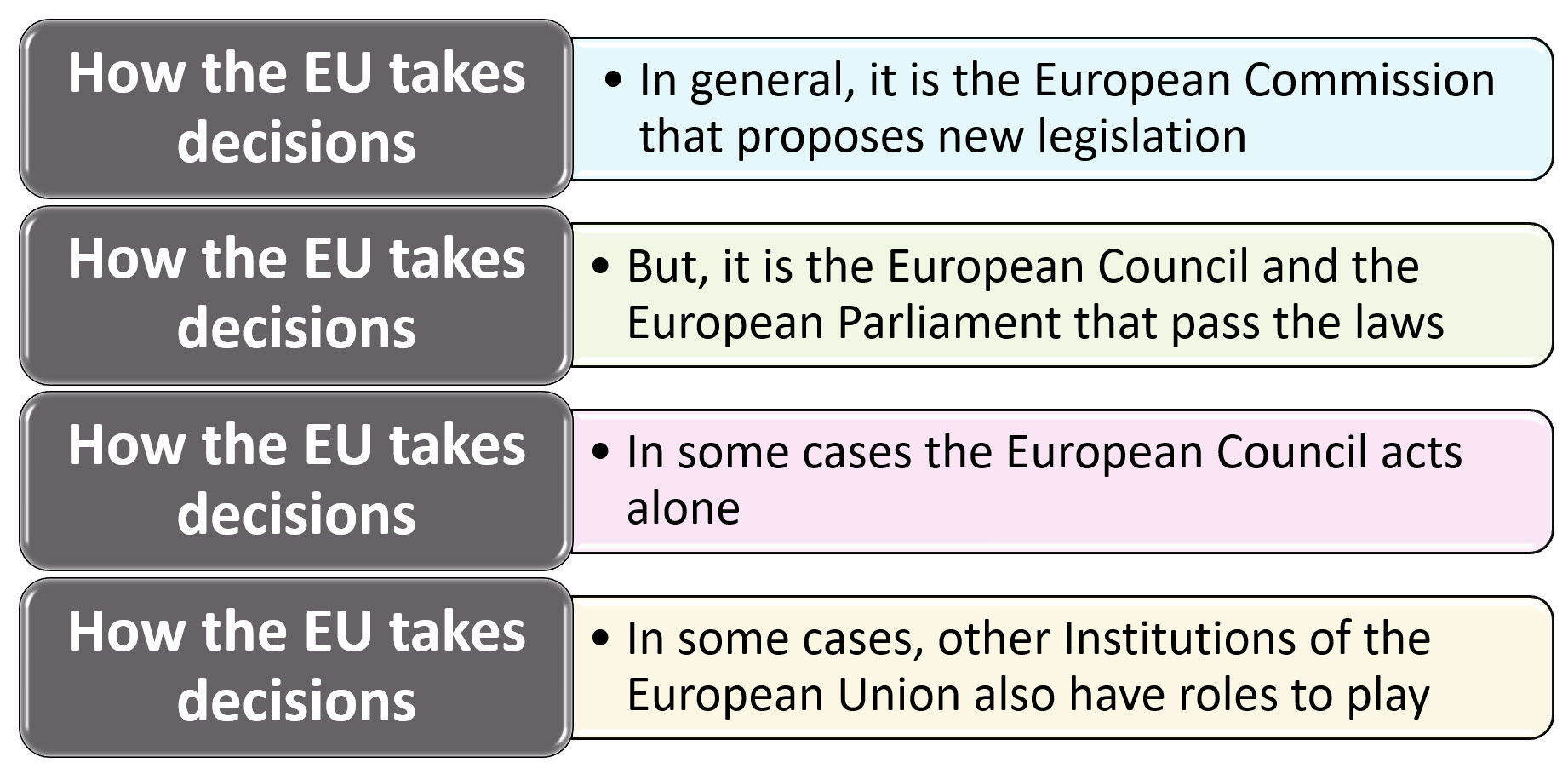

The rules and procedures for EU decision-Making are laid down in the Treaties.

Every proposal for a New European Law must be based on a specific Treaty article, which is referred to as the legal basis of the proposal.

This determines which legislative procedure must be followed;

The Treaties are the basis for everything the EU does.

The Treaties have been amended each time New Member States have joined.

From time to time the Treaties have also been amended to reform the European Union's Institutions and to give it New Areas of Responsibility.

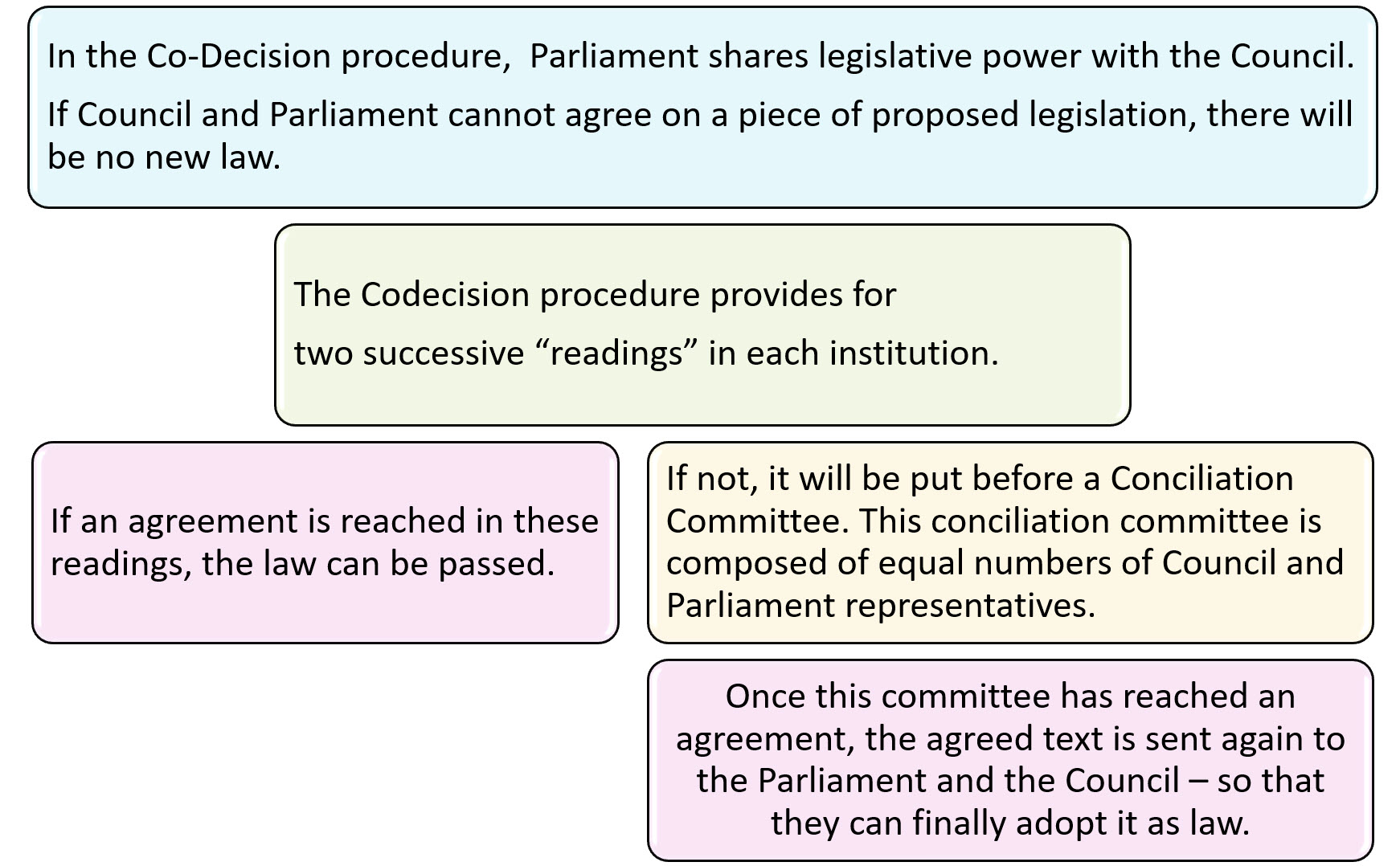

Co-Decision is the procedure used for most EU law-making.

In the Co-Decision procedure, Parliament shares legislative power with the Council.

If Council and Parliament cannot agree on a piece of proposed legislation, there will be no new law.

Most laws passed in Co-Decision are, in fact, adopted either at the first or the second reading as a result of good cooperation between the Institutions.

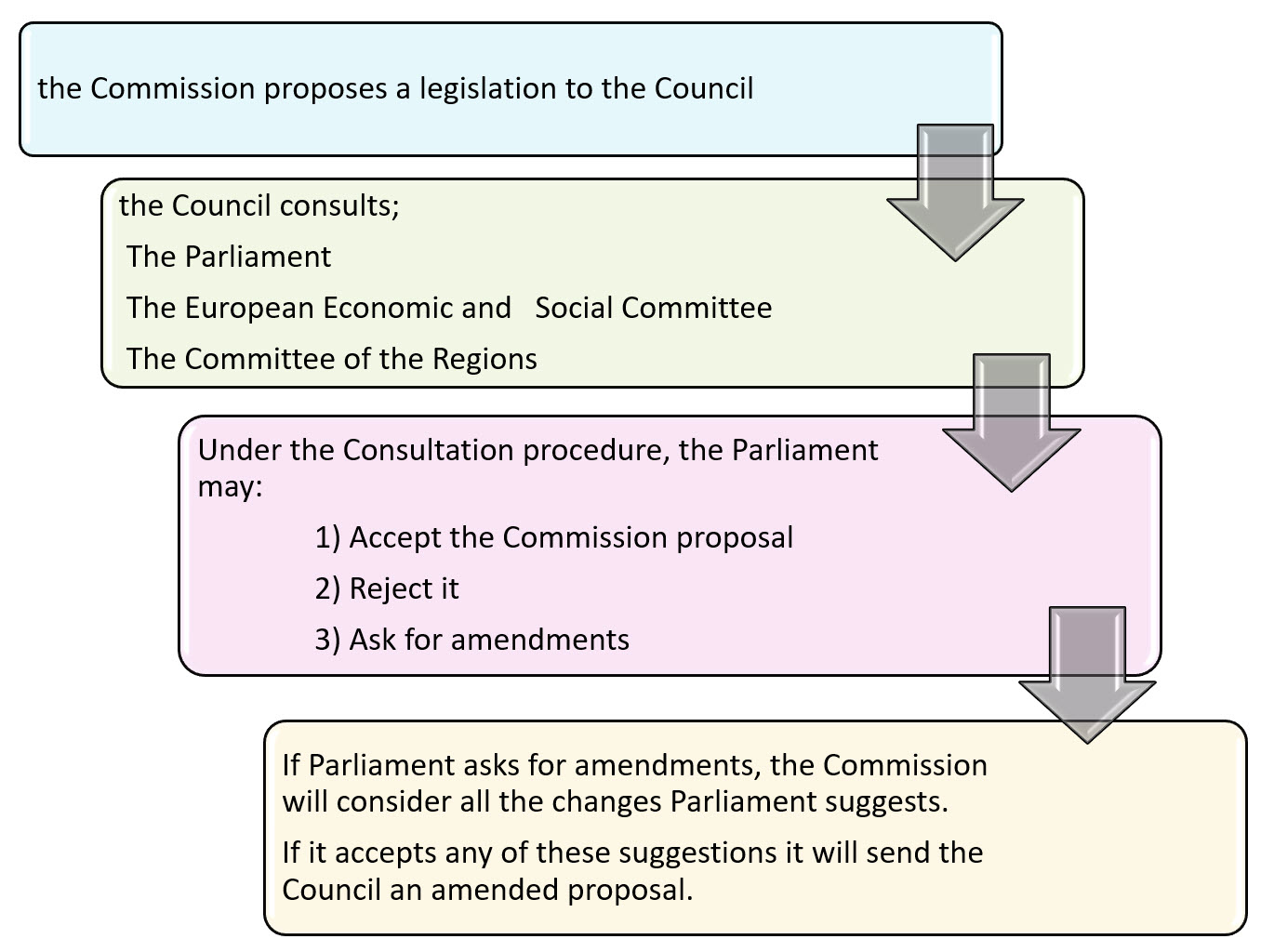

The Consultation Procedure is used in areas such as agriculture, taxation and competition.

Here are the steps of the Consultation Procedure:

Based on a proposal from the Commission, the Council consults;

Under the Consultation procedure, the Parliament may:

If the Parliament asks for amendments, the Commission will consider all the changes the Parliament suggests. If it accepts any of these suggestions It will send the Council an amended proposal.

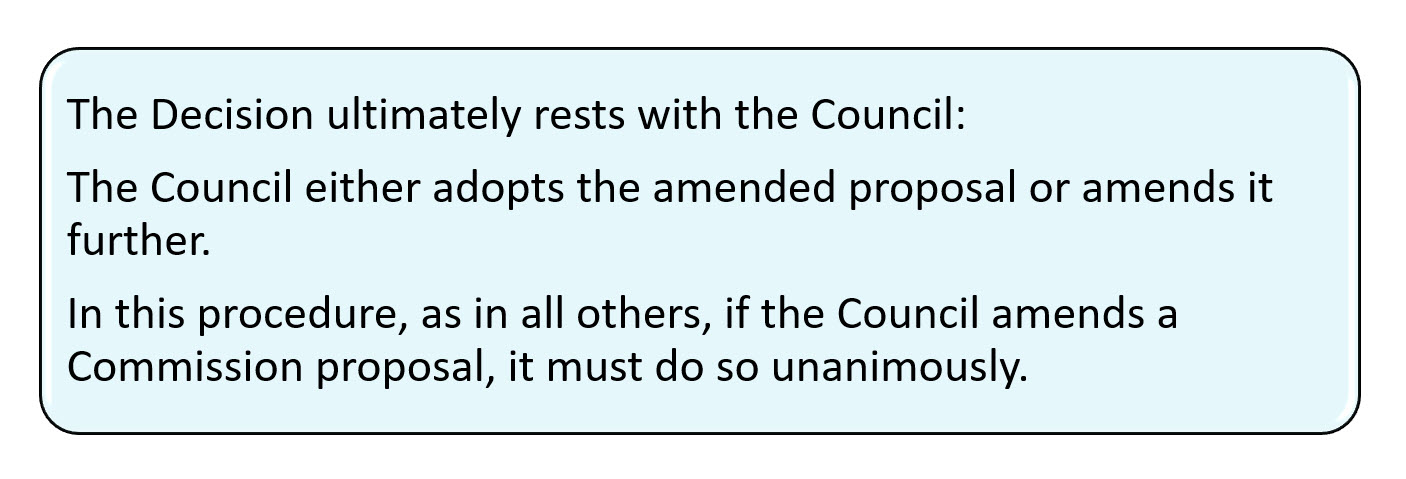

The decision ultimately rests with the Council; the Council either adopts the amended proposal or amends it further.

In this procedure, as in all others, if the Council amends a Commission proposal, it must do so unanimously.

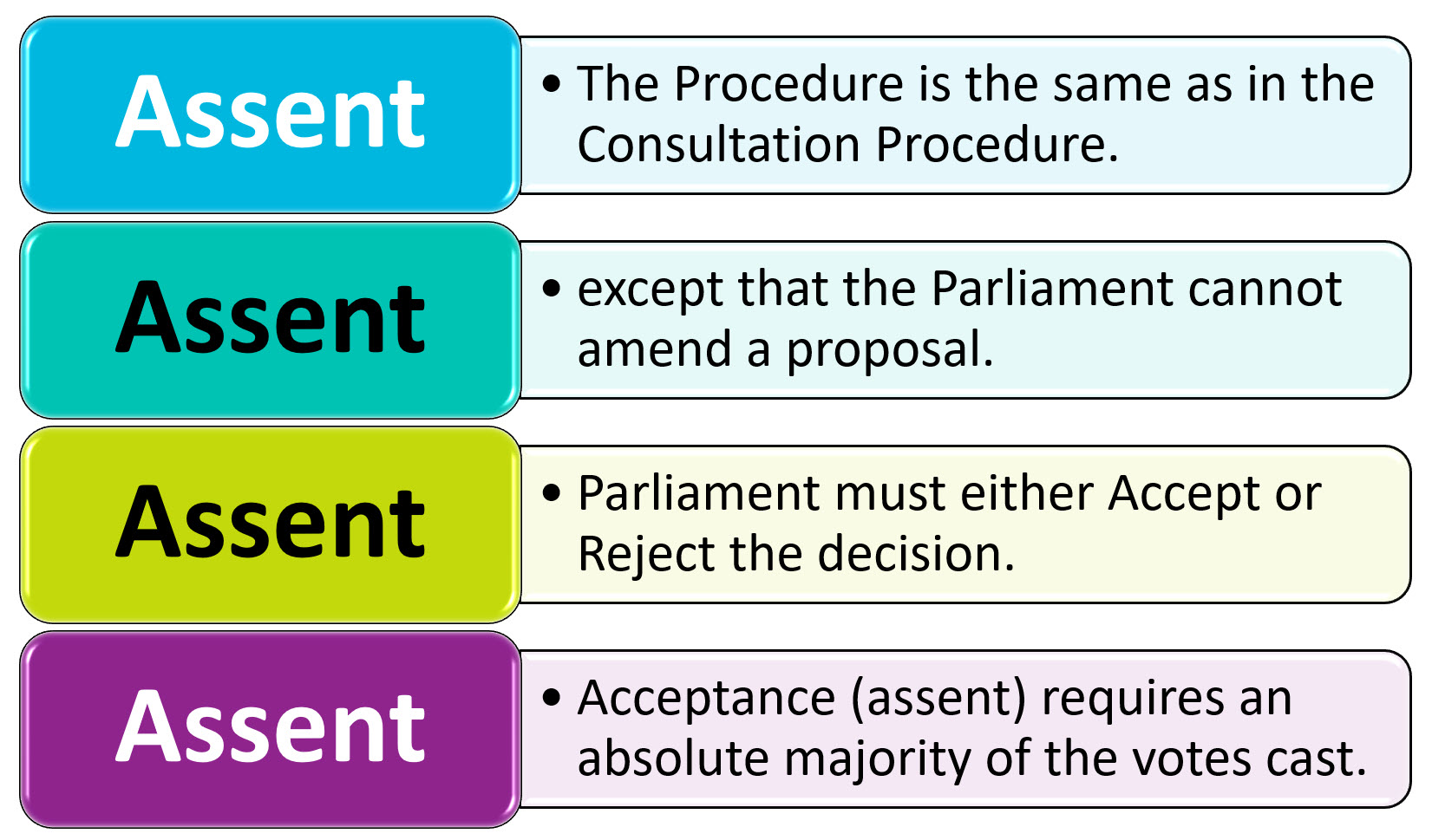

The Assent Procedure means that the Council has to obtain the European Parliament's assent before certain very important decisions are taken.

To Assent: to give approval to.

Please Note:

The President of the European Parliament

How is the Parliament’s work organised?

The MEPS and the Political Groups

Where is the Parliament based?

The European Parliament is the parliamentary institution of the European Union. The European Parliament (EP) is elected by the citizens of the European Union to represent their interests. Its origins go back to the 1950s and the founding Treaties. Since 1979 its members have been directly elected by the citizens of the EU.

Elections are held every five years, and every EU citizen is entitled to vote, and to stand as a candidate, wherever they live in the EU. Parliament thus expresses the democratic will of the Union’s nearly 500 million citizens and it represents their interests in discussions with the other EU institutions.

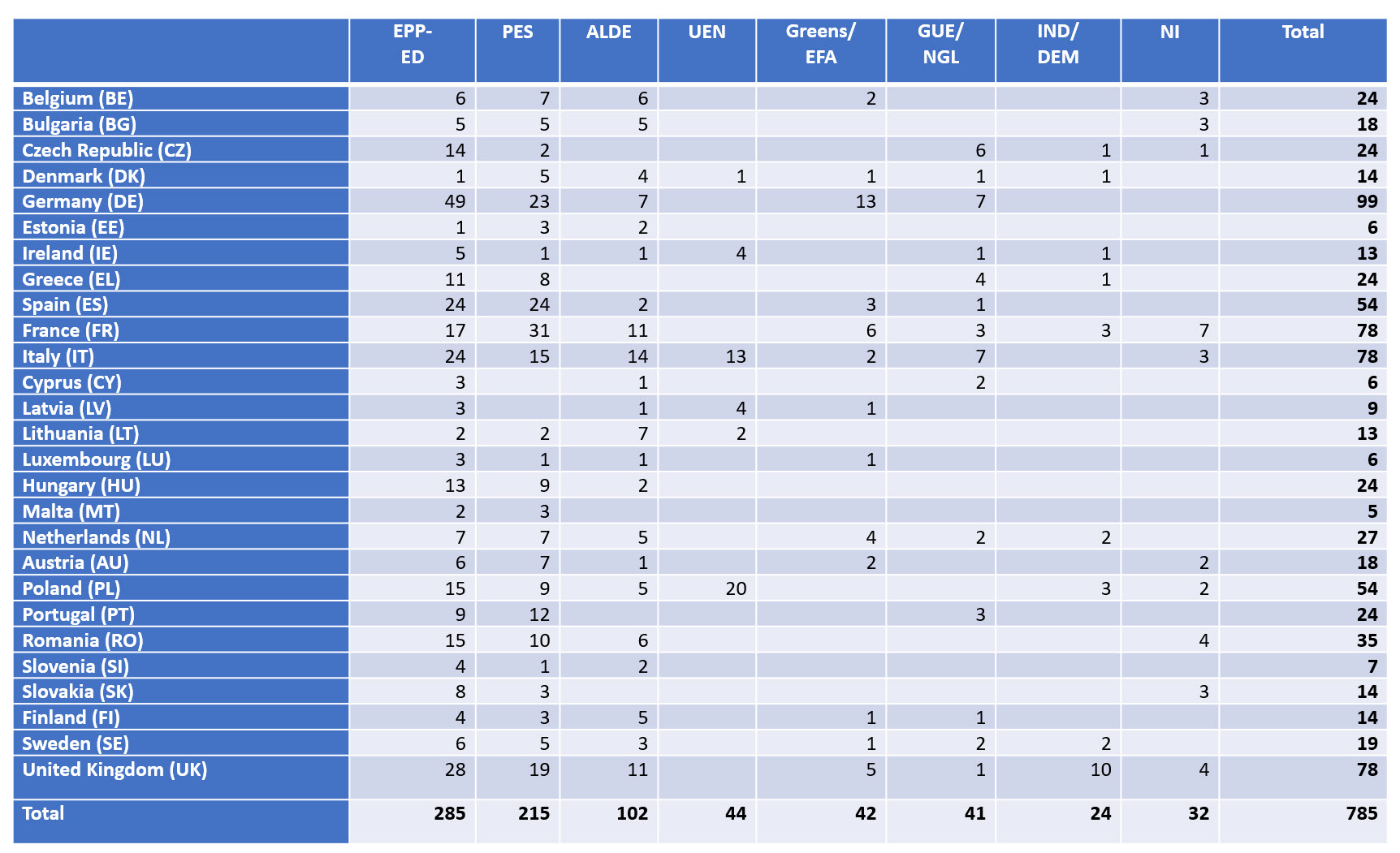

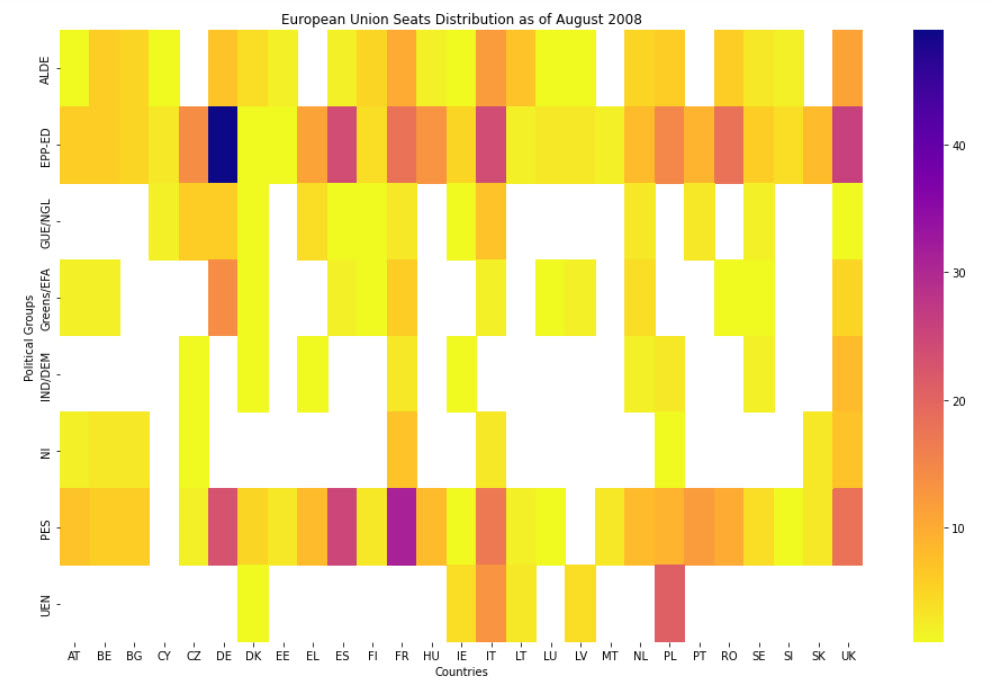

The latest elections were in June 2004. Parliament has 785 members from all 27 EU countries.

Information in this section, are taken from the booklet called 'The faces of the European Parliament', which is produced by the European Parliament's Directorate-General for Communication (ISBN 928232316-1) and also from the European Parliament's website: www.europarl.europa.eu.

The President of the European Parliament is elected for a renewable term of two and a half years, i.e. half the lifetime of a Parliamentary term. The President represents the European Parliament, vis-a-vis the outside world and in its relations with the other Community institutions. The President chairs the plenary sittings of Parliament, the Bureau of Parliament (including 14 Vice-Presidents) and the Conference of Presidents of political groups.

| From | To | President |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | 1960 | Robert Schuman |

| 1960 | 1962 | Hans Furler |

| 1962 | 1964 | Gaetano Martino |

| 1964 | 1965 | Jean Duvieusart |

| 1965 | 1966 | Victor Leemans |

| 1966 | 1969 | Alain Poher |

| 1969 | 1971 | Mario Scelba |

| 1971 | 1973 | Walter Behrendt |

| 1973 | 1975 | Cornelis Berkhouwer |

| 1975 | 1977 | Georges Spenale |

| 1977 | 1979 | Emilio Colombo |

| 1979 | 1982 | Simone Veil |

| 1982 | 1984 | Pieter Dankert |

| 1984 | 1987 | Pierre Pflimlin |

| 1987 | 1989 | Lord Plumb |

| 1989 | 1992 | Enrique Baron Crespo |

| 1992 | 1994 | Egon Klepsch |

| 1994 | 1997 | Klaus Hansch |

| 1997 | 1999 | Jose Maria Gil-Robles |

| 1999 | 2002 | Nicole Fontaine |

| 2002 | 2004 | Pat Cox |

| 2004 | 2007 | Josep Borrel Fontelles |

| 2007 | Hans-Gert Pöttering |

Reflections of Simone Veil -- the first president to be elected directly, in other words by universal suffrage.

"In the spring of 1979, I was Minister for Health and Social Security when, a few months before the first elections to the European Parliament by universal suffrage, President Giscard d'Estaing asked me if I would be willing to head a list of candidates for this election.

I accepted this honour without hesitation, having been a military supporter of European integration since the end of the war, regarding it as the only way to set the seal on reconciliation between France and Germany and avoid a recurrence of the tragedies of the past.

After the excellent result achieved by my list, President Giscard d'Estaing who was sensitive to symbols of reconciliation and hence aware of a former deportee, suggested to the other governments that I should be made President of the new Parliament, something that I had never imagined happening. That is how, on 13 July 1979, by an absolute majority in the second round, I came to be elected President of the new assembly.

The task that now faced me was not without its problems. First of all, the nature of the new Member's mandate had changed now that they were elected by universal suffrage, as opposed to the former situation in which members of the Assembly were representatives of the national parliaments. The democratic underpinning had now become more direct. In addition, Parliament's rules of procedure turned out to be inappropriate for its new role, not least in budgetary terms.

To this was added a geographical issue. Up to then the European Assembly had usually met in Luxembourg, where most of its officials also lived. In Strasbourg, the Parliament had neither its own chamber nor any offices, and therefore had to squat for one week each month in the premises of the Council of Europe, bringing all the necessary documents with it from Luxembourg. One can imagine that this peripatetic existence was not to the liking of some of the parlamentarians, so that I had to contain a certain level of disgruntlement. It took months for this modus operandi to become second nature. We still had to continue to hold a few sessions in Luxembourg. It was there that I remember with emotion welcoming the Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat not long before he was assasinated.

The Members of the European Parliament, as one can imagine, wanted to assert their new authority in budgetary matters. The budget that had been drawn up for 1980 turned out to have slightly exceeded the ceiling allocated by the treaties to the European Parliament. As the point in issue was combating world hunger, I unhesitantly declared this budget to have been duly adopted. The French Government immediately brought an action before the Court of Justice. It took some time for agreement to be reached between the Parliament, the Council and the national governments, particularly the one in Paris.

I remember the real interest that the new European Parliament aroused outside the Community in those now distant days. This interest and curiosity was all the greater because the Presidency of the Parliament was given to a woman, which at that time was still looked upon with some disapproval. I was able to observe this when I went to Lomé for the signing of the treaties with the African, Pacific and Caribbean countries.

I remember that both inside and outside the Community I always received a warm welcome, including in the United States, Canada, China and Japan. Whenever possible I involved the Commission permanent representatives in these visits. Throughout a presidency that lasted two and a half years, I never had any difficulty in always being seen by myself and others as standing above party divisions and representing the whole of Parliament.

In short, this sometimes difficult, always fascinating presidency has remained the most rewarding period of my life. I look back on it with nostalgia, as I do on the subsequent years I spent at the European Parliament before returning to the French government in 1993." Simone Veil

Excerpt from 'Reflections of former Presidents of the European Parliament, EU Publications Office, ISBN 978-92-823-2450-9'.

Hans-Gert Pöttering was elected President of the EP in 2007 and is to hold that post until the 2009 elections.

The European Parliament speaks on behalf of nearly 500 million

European citizens from the

27 Member States of the European Union.

...

...

The European Union represents a unique model of life and society. It is based on equal rights and solidarity. Its foundation is our common values, particularly respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy and compliance with the law. The European Parliament defends these rights beyond the borders of the European union, all over the world. In many countries, even outside the European Union, the voice of the European Parliament has considerable moral authority.

The Berlin declaration, adopted on the 50th anniversary of the signature of the Treaties of Rome, states:

'We are, for our greater happiness, united'.

We are leaving behind us a past in which European history was blighted by war, and looking to the future, for which we in the European Union now have a shared responsibility and in which we shall realise our ideals and values.

Only together can we overcome the challenges of the future, for example find ways of defending our ideal of society, ensuring growth and employment, protecting the climate and the environment, and combating terrorism and organised crime.

...

Hans-Gert Pöttering

President of the European Parliament 2007—2009

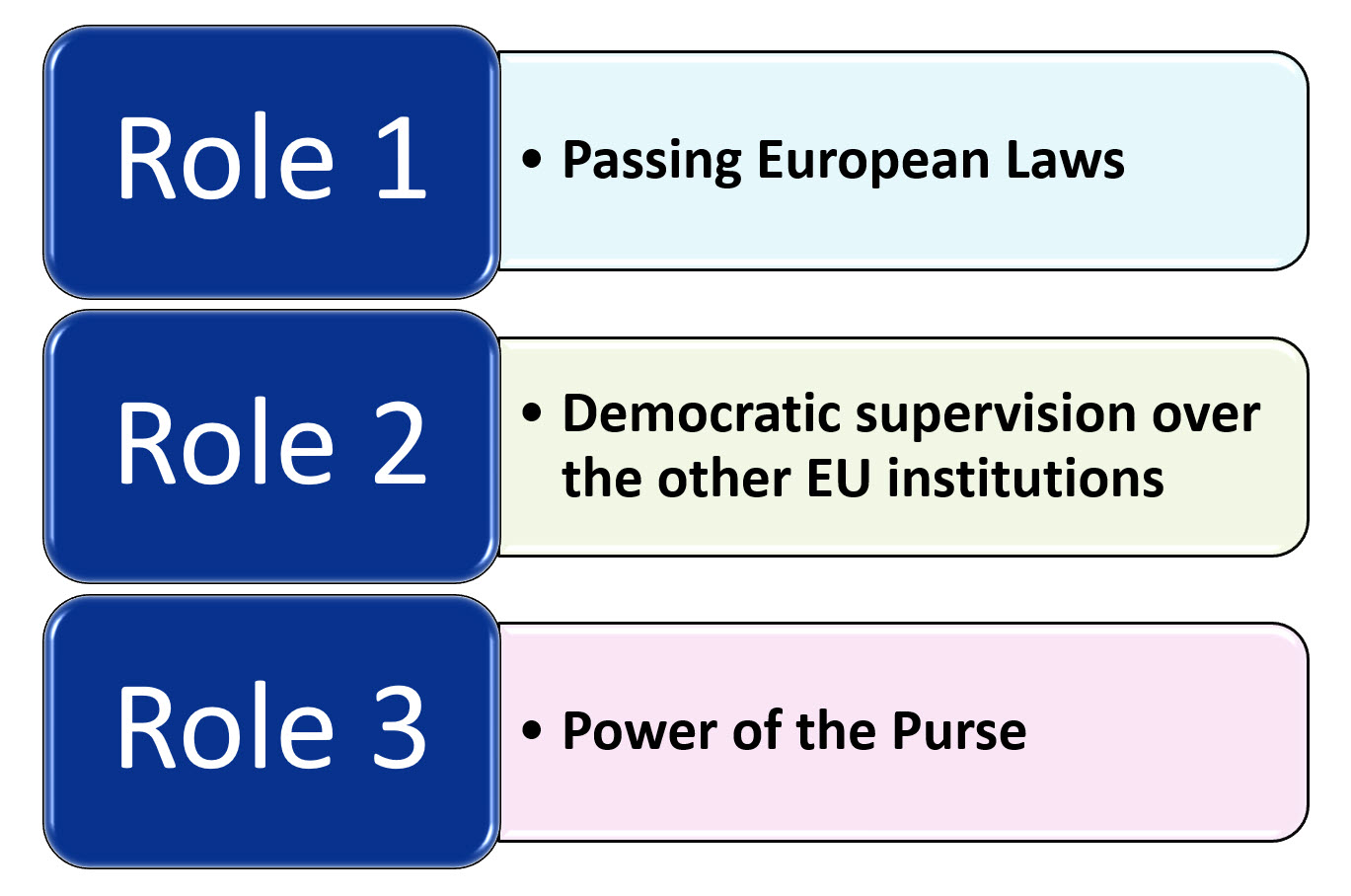

Parliament passes European laws jointly with the Council in many policy areas. The fact that the EP is directly elected by the citizens of the EU helps guarantee the democratic legitimacy of the European law.

We have already seen the procedures used for passing new EU laws under the heading "How EU takes Decisions".

The most common procedure for adopting, i.e passing EU legislation is codecision.

Codecision Procedure places the European Parliament and the Council on an equal footing. Codecision Procedure applies to laws in a wide range of fields.

In some fields such as agriculture, economic policy, visas and immigration, the Council alone legislates, but it has to consult Parliament – the Consultation Procedure to pass new EU laws.

Also for certain important decisions such as allowing new countries to the EU, the Parliament's assent is required – the Assent Procedure.

Parliament also provides impetus for new legislation by examining the Commission's annual work programme, considering what new laws would be appropriate and asking the Commission to put forward proposals.

Parliament exercises democratic supervision over the other EU Institutions in several ways.

Parliament also monitors the work of the Council. MEPs regularly ask the Council questions, and the President of the Council attends the EPs plenary sessions and takes part in important debates.

Parliament can exercise further democratic control by examining petitions from citizens and setting up committees of inquiry.

Finally, Parliament provides input to every EU summit – i.e. the European Council meetings. At the opening of each summit, the President of Parliament is invited to express Parliament’s views and concerns about topical issues and the items on the European Council’s agenda.

Parliament shares with the Council authority over the EU budget. The EU's annual budget is decided jointly by Parliament and the Council. The budget does not come into force until it has been signed by the President of the Parliament.

Parliament's "Committee on Budgetary Control" monitors how the budget is spent. In addition, the Parliament each year decides whether to approve the Commission's handling of the budget. This approval process is technically known as 'granting a discharge'.

MEPs debate the Commission's proposals in committees that specialise in particular areas of EU activity and on the basis of "a report prepared by one of the committee members", the so-called rapporteur.

The report gives the background and the pros and cons of the proposal. The issues for debate are also discussed by the political groups.

Each year, 12 four-day plenary sessions are held in Strasbourg, and six two-day sessions are held in Brussels.

At these sessions;

Other agenda items may include;

Please Note:

| Code | Name | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| EPP-ED | Group of the European People's Party(Christian Democrats) and European Democrats |

|

| PES | Socialist Group in the European Parliament |  |

| ALDE | Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

|

| UEN | Union for Europe of the Nations Group |

|

| Greens/EFA | Group of Greens/European Free Alliance |

|

| GUE/NGL | Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left |

|

| IND/DEM | Independence/Democracy Group |

|

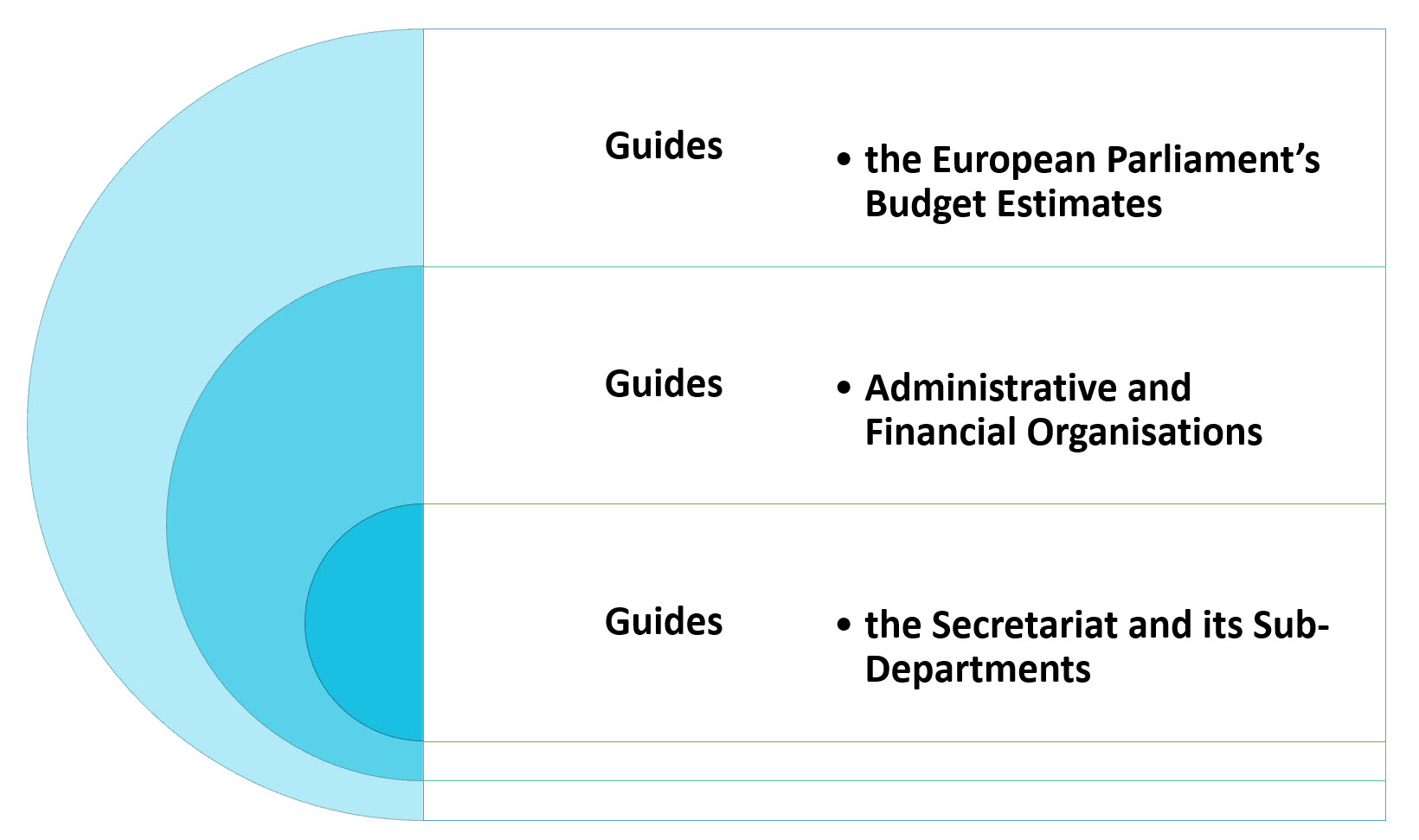

The Conference of the Presidents is made up of;

The Conference of the Presidents organises practical aspects of Parliament's work and decides on all questions relating to legislative planning.

It also has an important role to play in the relations between the European Parliament and the other Community institutions, third countries and extra-Community organisations.

The Bureau is made up of;

The Bureau Guides Parliament's Internal Functioning.

Plenary Work for the Parliament's plenary sittings takes place in Parliament's 20 Committees which cover everything from women's rights to health and consumer protection.

Committee on Foreign Affairs chaired by Jacek SARYUZS-WOLSKI of EPP-ED, PL, and its subcommittees;

Committee on Budgetary Control chaired by Herbert BÖSCH of PES, AT.

Temporary Committee on Climate Change chaired by Guido SACCONI of PES, IT.

EU-Croatia chaired by Pal SCHMITT of EPP-DE, HU.

EU-Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia chaired by Antonios TRAKATELLIS of EPP-ED, EL.

EU-Turkey chaired by Joost LAGENDIJK of Greens/EFA, NL.

ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly chaired by Glenys KINNOCK of PES, UK.

Euro-Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly (EUROMED) chaired by Hans Gert PÖTTERING of EPP-ED, DE.

The European Parliament is assisted by a Secretariat.

The Secretariat's establishment plan and the administrative and financial rules for officials and other staff are drawn up by the Bureau.

Below is a photo of the EU Complex in Luxembourg.

The Secretary-General of the European Parliament is Harald Romer.

Some of the Directorate-Generals of the Secretariat are;

The European Parliament has three places of work:

♣ Luxembourg is home to the Administrative Offices — the General Secretariat.

♣ Meetings of the whole Parliament, known as Plenary Sessions, take place in Strasbourg and sometimes in Brussels.

♣ Committee meetings are also held in Brussels.

Please Note:

The Council of the European Union

Which Ministers Attend Which Meeting

Exception to Council Configurations

Power of Each Council Minister

SUMMIT of the European Council

Three 'Councils': Which is Which?

How is the Council’s work organised?

Altogether, there are nine different Council Configurations.

The EU's relations with the rest of the world are dealt with by the 'General Affairs and External Relations Council'.

But this Council Configuration also has wider responsibility for General Policy Issues.

Therefore, its meetings are attended by, whichever Minister or State Secretary each Government chooses.

Power of Each Council Minister

Democratic Legitimacy of the Council's Decisions

The European Council / Summit

Up to four times a year

The European Council / Summit

These SUMMIT meetings set overall EU Policy and resolve issues that could not be settled at a lower level, i.e. by the Ministers at normal Council of the European Union Meetings.

The European Council / Summit

Given the importance of the European Council discussions, they often go on late into the night and attract a lot of media attention.

It’s easy to get confused about which European body is which – especially when very different bodies have very similar names, such as these three 'Councils'.

The Council of Europe - not an EU institution at all

The Council of the European Union

The Council of Europe - not an EU institution at all

This is not an EU institution at all.

It is an intergovernmental organisation which aims (amongst other things) to protect human rights, to promote Europe's cultural diversity and to combat social problems such as racial prejudice and intolerance.

It was set up in 1949 and one of its early achievements was to draw up the European convention on Human Rights.

To enable citizens to exercise their rights under that convention, it set up the European Court of Human Rights.

The Council of Europe now has 47 member countries, including all 27 European Union countries, and its headquarters is the Palais de l'Europe in Strasbourg (France).

The European Council

The European Council means;

It depends on the political system of each country whether their participant is the President and/or the Prime Minister.

The European Council meets, in principle, four times a year to agree overall EU policy and to review progress.

The European Council is the Highest Level policy making body in the European Union, which is why its meetings are often called 'SUMMIT's.

The Council of the European Union

Formerly known as the Council of Ministers, this institution consists of Government Ministers from all the EU countries.

The Council of the European Union meets regularly to take detailed decisions and to pass EU laws.

A full description of the work of The Council of the European Union is given in this Business Narrative of The Story of the European Union.

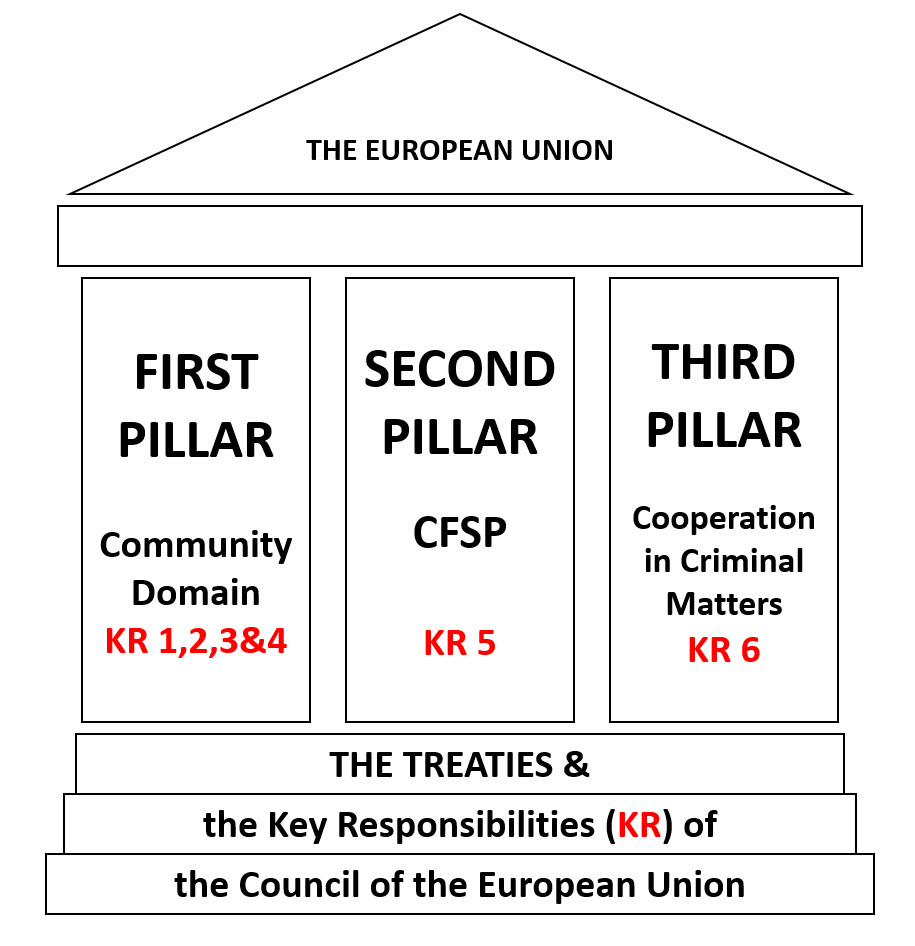

The Council has six Key Responsibilities:

KR 1 To pass EU laws – jointly with the European Parliament in many policy areas.

KR 2 To coordinate the broad economic and social policies of the Member States.

KR 3 To conclude international agreements between the EU and other countries or international organisations.

KR 4 To approve the EU’s budget, jointly with the European Parliament.

KR 5 To define and implement the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) based on guidelines set by the European Council.

KR 6 To coordinate cooperation between the National Courts and Police Forces in criminal matters.

Most of these Responsibilities, KR 1, KR2, KR 3, KR 4, relate to the Community Domain – i.e. areas of action where the member states have decided to pool their sovereignty and delegate decision making powers to the EU Institutions.

This domain is the FIRST PILLAR of the EU.

However, the last two responsibilities, KR 5 and KR 6, relate largely to areas in which the EU countries Have Not delegated their powers but are simply working together.

This is called intergovernmental cooperation and it covers the SECOND and THIRD PILLARS of the EU.

The bulk of the Council's work is in passing legislation in areas where the EU has pooled its sovereignty.

The most common procedure for this is 'Codecision', where EU legislation is adopted jointly by the Council and Parliament on the basis of a proposal from the Commission.

In some areas, the Council has the final word but only on the basis of a Commission proposal and only after having taken into account the views of the Commission and the Parliament.

The EU countries have decided that they want an overall economic policy based on close coordination between their national economic policies.

This coordination is carried out by the economics and finance ministers, who collectively form the Economic and Financial Affairs (Ecofin) Council.

They also want to create more jobs and to improve their education, health and social protection systems.

Although each EU country is responsible for its own policy in these areas, they can agree on common goals and learn from each other's experience of what works best.

This process is called the Open Method of Coordination and it takes place within the Council.

Each year, the Council 'concludes' i.e. officially signs) a number of agreements between the European Union and non-EU countries, as well as with international organisations.

These agreements may cover broad areas such as trade, cooperation and development or they may deal with specific subjects such as textiles, fisheries, science and technology, transport, etc.

In addition, the Council may conclude conventions between the EU Member States in fields such as taxation, company law or consular protection.

Conventions can also deal with cooperation on issues of freedom, security and justice.

The EU's annual budget is decided jointly by the Council and the European Parliament.

The EU countries are working to develop a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

But Foreign Policy, Security and Defence are matters over which the individual National Governments retain independent control.

However, the EU countries have recognised the advantages of working together on these issues, and the Council is the main forum in which this 'Intergovernmental Cooperation' takes place.

This cooperation not only covers defence issues, but also crisis management tasks, such as humanitarian and rescue operations, peacekeeping and peacemaking in trouble spots.

The EU countries try to mobilise and coordinate military and police forces, so that they can be used in coordination with diplomatic and economic action.

Through these mechanisms, the EU has helped to maintain peace, build democracy and spur economic progress in places as far apart as Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the countries of south-eastern Europe.

EU citizens are free to live and work in whichever EU country they choose, so they should have equal access to civil justice everywhere in the European Union.

National courts therefore need to work together to ensure, for example, that a court judgment delivered in one EU country in a divorce or child custody case is recognised in all other EU countries.

Freedom of movement within the EU is of great benefit to law-abiding citizens, but it is also exploited by international criminals and terrorists.

To tackle cross-border crime requires cross-border cooperation between the national courts, police forces, customs officers and immigration services of all EU countries.

They have to ensure, for example:

Issues such as these are dealt with by the Justice and Home Affairs Council — i.e. the Ministers for Justice and of the Interior.

The aim is to create a 'Single Area of Freedom, Security and Justice' within the EU's borders.

The Presidency is held by each Member State, on a rotating basis, for a period of six months – January to June and July to December.

In In other words, each EU country in turn takes charge of the Council agenda and chairs all the meetings for a six-month period, promoting legislative and political decisions and brokering compromises between the Member States.

| Year | First Half | Second Half |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Slovenia | France |

| 2009 | Czech Republic | Sweden |

| 2010 | Spain | Belgium |

| 2011 | Hungary | Poland |

| 2012 | Denmark | Cyprus |

| 2013 | Ireland | Lithuania |

| 2014 | Greece | Italy |

| 2015 | Latvia | Luxembourg |

| 2016 | Netherlands | Slovakia |

| 2017 | Malta | United Kingdom |

| 2018 | Estonia | Bulgaria |

| 2019 | Austria | Romania |

| 2020 | Finland |

The Presidency is assisted by the General Secretariat, which prepares and ensures the smooth functioning of the Council’s work at all levels.

In 2004, Javier Solana was reappointed Secretary-General of the Council. He is also High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and in this capacity he helps coordinate the EU's action on the world stage.

The Secretary-General is assisted by a Deputy Secretary-General in charge of managing the General Secretariat.

In Brussels, each EU country has a Permanent Team (Representation) that represents it and defends its national interest at EU level.

The Head of each Representation is, in effect, that Country's Ambassador to the EU.

These Ambassadors are known as Permanent Representatives and meet weekly within the Permanent Representatives Committee (Coreper).

The role of this committee is to prepare the work of the Council, with the exception of most agricultural issues, which are handled by the Special Committee on Agriculture.

Coreper is assisted by a number of working groups, attended by officials from the representations or national administrations.

The Council is assisted by a separate structure in matters of Security and Defence:

Decisions in the Council are taken by vote.

The bigger the country's population, the more votes it has, but the numbers are weighted in favour of the less populous countries:

| France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom | 29 |

| Poland and Spain | 27 |

| Romania | 14 |

| Netherlands | 13 |

| Belgium, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary and Portugal | 12 |

| Austria, Bulgaria, Sweden | 10 |

| Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Lithuania and Slovakia | 7 |

| Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg and Slovenia | 4 |

| Malta | 3 |

| Total | 345 |

In some particularly sensitive areas such as common foreign and security policy, taxation, asylum and immigration policy, Council decisions have to be unanimous.

In other words, each member state has the power of veto in these areas.

On most issues, however, the Council takes decisions by Qualified Majority Voting.

A Qualified Majority is reached:

In addition, a member state may ask for confirmation that the votes in favour represent at least 62% of the total population of the Union.

If this is found not to be the case, the decision will not be adopted.

Please Note:

Where is the Commission based?

How is the Commission's work organised?

The Commission is independent of national governments. Its job is to represent and uphold the interests of the EU as a whole. It drafts proposals for new European laws, which it presents to the European Parliament (EP) and the Council.

It is also the EU’s executive arm — in other words, it is responsible for implementing the decisions of Parliament and the Council. That means managing the day-to-day business of the European Union: implementing its policies, running its programs and spending its funds.

Like the EP and the Council, the European Commission was set up in the 1950s under the EU’s founding Treaties.

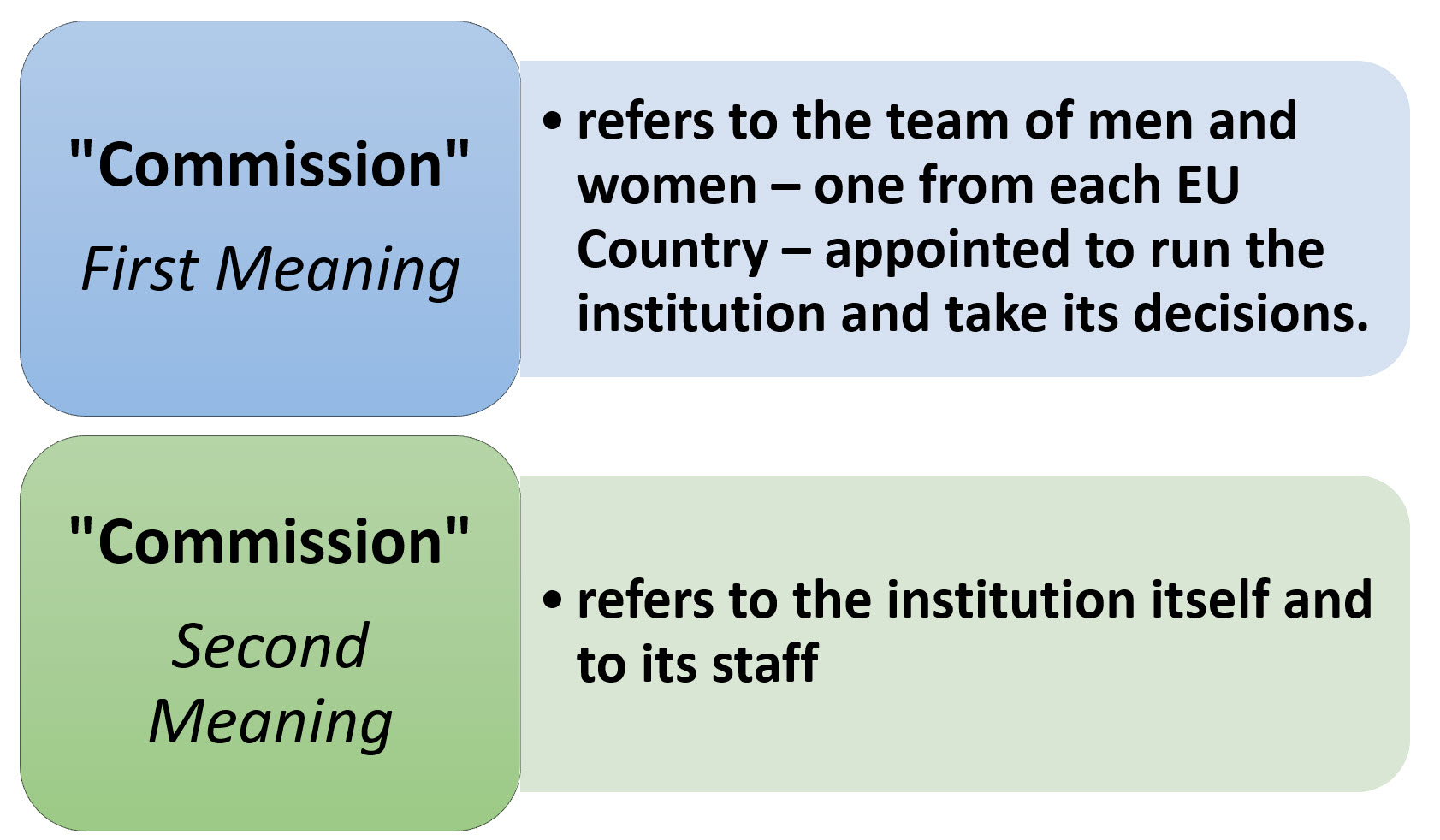

The term 'Commission' is used in two senses:

Informally, the appointed members of the Commission are known as 'Commissioners'.

They have generally held Political Positions in their Countries of Origin and many have been Government Ministers.

But, as Members of the Commission they are committed to acting in the interests of the Union as a whole and Not taking instructions from National Governments.

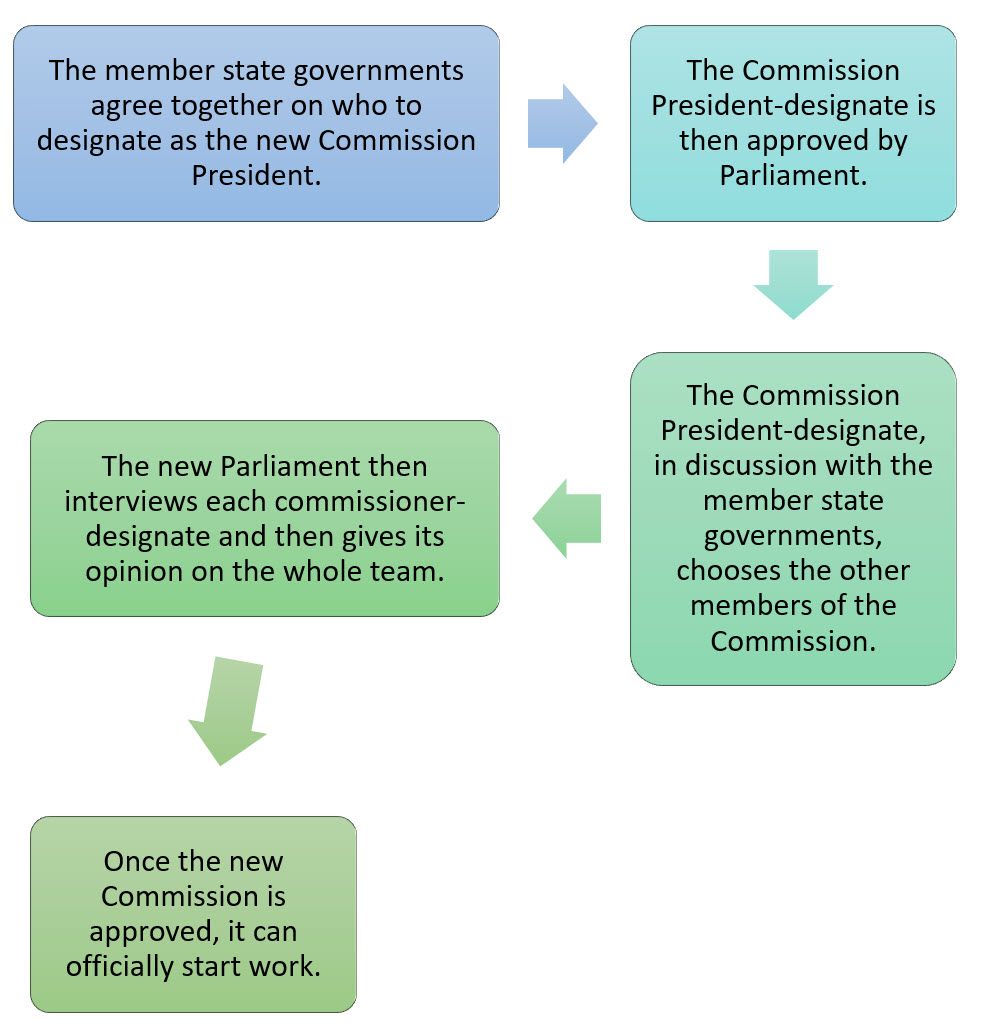

A new Commission is appointed every five years within six months of the elections to the European Parliament.

The procedure is as follows:

The present Commission's term of office runs until 31 October 2009. Its President is José Manuel Barroso.

The Commission remains politically accountable to Parliament, which has the power to dismiss the whole Commission by adopting a motion of censure. Individual members of the Commission must resign if asked to do so by the President and the other commissioners approve.

The Commission is represented at all sessions of Parliament, where it must clarify and justify its policies. It also replies regularly to written and oral questions posed by MEPs.

The day-to-day running of the Commission is in the hands of administrative officials, experts, translators, interpreters and secretarial staff.

There are approximately 23 000 of these European civil servants.

That may sound a lot, but in fact it is fewer than the number of staff employed by a typical medium-sized city council in Europe.

The 'seat' of the Commission is in Brussels (Belgium), but it also has offices in Luxembourg, representations in all EU countries and delegations in many capital cities around the world.

The European Commission has Four Main Roles:

The Commission has the Right of Initiative.

In other words, the Commission alone is responsible for drawing up proposals for new EU legislation, which it presents to Parliament and the Council.

These proposals must aim to defend the interests of the Union and its citizens, not those of specific countries or industries.

Before making any proposals, the Commission must be aware of new situations and problems developing in Europe, and it must consider whether EU legislation is the best way to deal with them.

That is why the Commission is in constant touch with a wide range of interest groups and with two advisory bodies;

It also takes the opinions of National Parliaments and Governments into account.

The Commission will propose action at EU level only if it considers that a problem cannot be solved more efficiently by National, Regional or Local action.

This approach of dealing with issues at the lowest possible level is called the Subsidiarity Principle.

If the Commission concludes that EU legislation is needed, then it drafts a proposal that it believes will deal with the problem effectively and satisfy the widest possible range of interests.

To get the technical details right the Commission consults experts, via various advisory committees and consultative groups.

Frequently, it publishes Green and White Papers, holds hearings, seeks the views of civil society and Commissions' specialist expert reports, and often consults the public directly before it makes a proposal in order to ensure that it has as complete a picture as possible.

As the European Union’s executive body, the Commission is responsible for managing and implementing the EU Budget.

Most of the actual spending is done by National and Local authorities, but the Commission is responsible for supervising it — under the watchful eye of the Court of Auditors.

Both institutions aim to ensure good financial management.

Only if it is satisfied with the Court of Auditors' annual report, does the European Parliament grant the Commission discharge for implementing the Budget.

The Commission also has to implement decisions taken by Parliament and the Council, such as those relating to the;

It also plays a major role in Competition Policy in order to ensure that Businesses operate on a level playing field.

The Commission may prohibit mergers between companies if it thinks they will lead to unfair competition.

The Commission also has to make sure that EU countries do not distort competition through excessive subsidies to their industries.

The Commission acts as Guardian of the Treaties.

This means that the Commission, together with the Court of Justice, is responsible for making sure EU law is properly applied in all the Member States.

If it finds that an EU Country is not applying an EU Law, it launches a process called the Infringement Procedure.

The first step is to send the government an official letter, saying why the Commission considers this country is infringing EU law and setting it a Deadline for Sending a Detailed Explanation.

If the Member State does not have a satisfactory explanation or put matters right, the Commission will send another letter confirming that EU law has been infringed and setting a Deadline for it to be Corrected.

If the Member State still fails to comply, the Commission will refer the matter to the Court of Justice to decide.

The Court's Judgements are Binding on the Member States and the EU Institutions.

In cases where Member States continue failing to adhere to a judgment, the Court can impose Financial Sanctions.

The European Commission is an important spokesperson for the European Union on the International Stage.

It is the voice of the EU in;

The Commission also speaks and negotiates on behalf of the EU in areas where the Member States have pooled sovereignty.

This is done on the basis of agreements reached in advance with the Member States.

It is up to the Commission President to decide which Commissioner will be responsible for which Policy Area, and to reshuffle these responsibilities (if necessary) during the Commission's term of office.

The Commission generally meets once a week, usually on Wednesdays, and usually in Brussels. Each item on the agenda is presented by the Commissioner Responsible for that policy area, and the whole team then takes a Collective Decision on it.

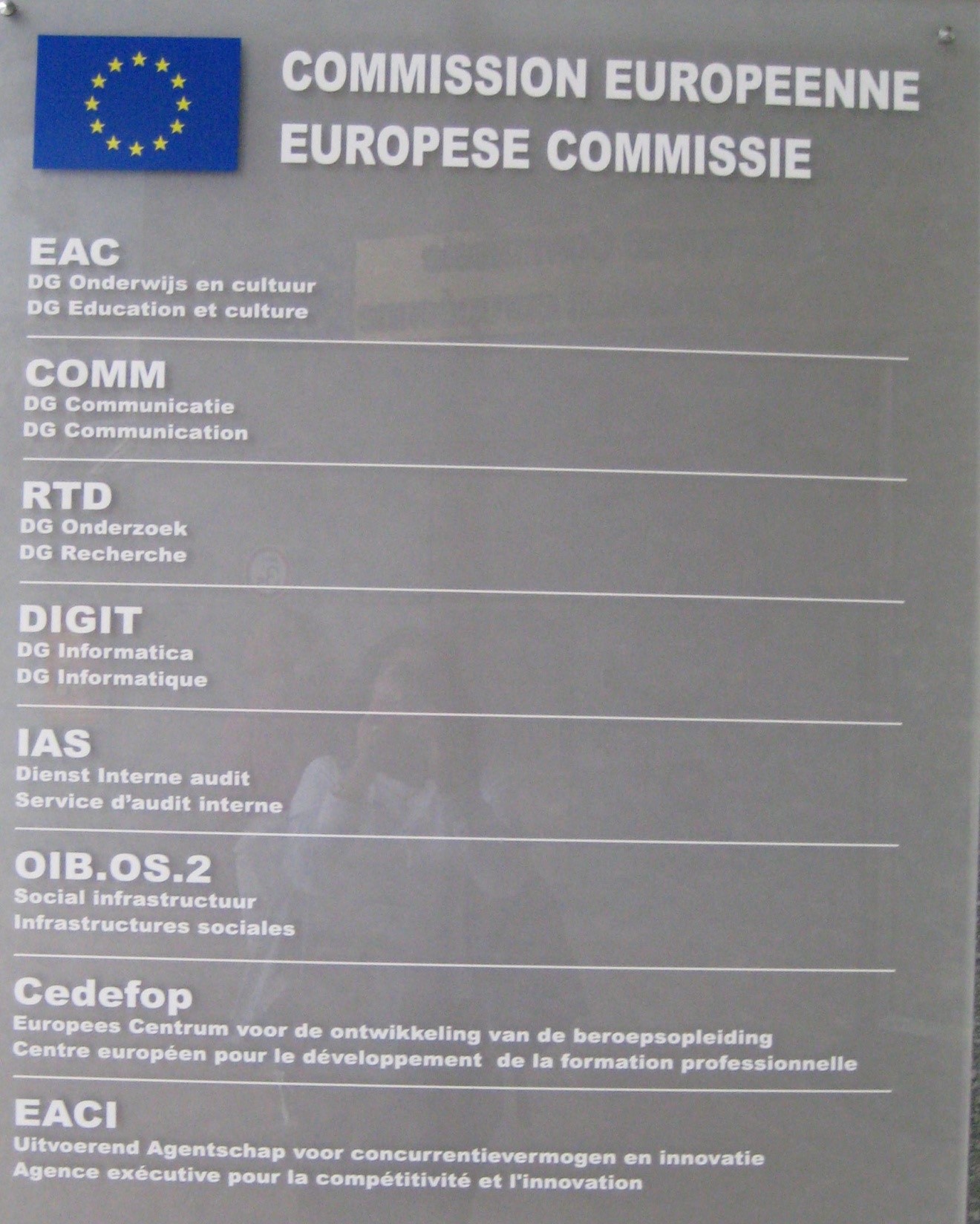

The Commission’s staff is organised in Departments, known as Directorates-General (DGs) and Services (such as the Legal Service).

Each DG is responsible for a particular Policy Area and is headed by a Director-General who is answerable to one of the Commissioners.

Overall coordination is provided by the Secretariat-General, which also manages the weekly Commission meetings. It is headed by the Secretary General, who is answerable directly to the President.

It is the DGs that actually devise and draft Legislative Proposals, but these proposals become official only when 'adopted' by the Commission at its weekly meeting.

The Procedure is roughly as follows:

This sums up our Business Narrative.